Water is the natural resource we never really think about. Yet, we are all responsible for taking good care of it, for making sure it’s secure and available for future generations.

The San Antonio region has always depended on the Edwards Aquifer for its water needs. The Edwards, one of the most abundant artesian aquifers in the world, supplies the San Pedro and San Antonio springs, which until the middle of the 20th century provided the base flow for San Pedro Creek and the San Antonio River. Those springs were the site of Native-American encampments centuries ago and were the reason that the Spanish established San Antonio in 1718.

Early Irrigation Canals

Early Irrigation Canals

The primary water distribution system in the area was the acequías, or irrigation canals. The first canal, Pajalache or Concepcíon, became operational about 1720. The acequías were supplemented by shallow wells and provided water for both irrigation and consumption. These canals also began to serve as a de facto sewer system. Early San Antonians merely deposited their garbage and other wastes into the canals where they flowed downstream.

In 1836, the San Pedro acequía was reserved for drinking and cooking water only; penalties were established for using it for bathing or as a sewer. Although crude, this water and wastewater operation served the city’s needs until 1866 when a severe cholera epidemic spurred real efforts to establish a satisfactory and safe water supply system.

Water Supply System Development

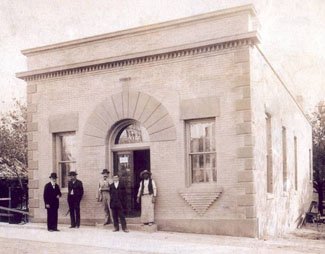

Many water development proposals were discussed and subsequently discarded over the years until the city finally entered into a water supply contract with J.B. LaCoste and Associates on April 3, 1877. LaCoste constructed a pumphouse near the headwaters of the San Antonio River in what is now Brackenridge Park. Water pressure operated a pump which lifted water to a reservoir near the Old Austin Road on the present site of the San Antonio Botanical Garden. This site was high enough for the water to flow by gravity into the distribution system.

In 1883, a new company led by George W. Brackenridge acquired the water system. Recognizing that the source of the springs was possibly a subterranean reservoir under high pressure, Brackenridge proposed that his firm purchase property along the river and drill a well.

In 1889, the first artesian well was bored in what later became Brackenridge Park. Two years later an 8-inch discovery well was drilled to a depth of 890 feet at Market Street and the San Antonio River. By 1900, all of the system’s water was obtained from artesian wells linked directly to the distribution system.

Foreign Ownership

Foreign Ownership

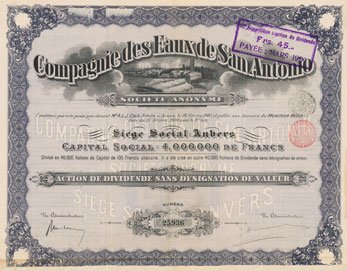

In 1905, George Brackenridge sold his interests in the water company to George Kobusch of St. Louis, Mo. At that time, the name was changed to the San Antonio Water Supply Company.

Shortly thereafter, Kobusch sold the business to a Belgian syndicate. While it was under foreign ownership, the water company was known as “Compagnie des Eaux de San Antonio” and was managed by the Mississippi Valley Trust Company of St. Louis. Partly to recover some of their financial losses from World War I, the Belgians sold the waterworks to a group of local investors in 1920.

City Water Board

Contract and rate disagreements marred the relationship between the city and the new water entity. In 1924, the company demanded a rate increase and because an agreement could not be reached, the new rates were put into effect and the City was prohibited from interfering.

This situation prompted the city to issue $7 million in revenue bonds so it could purchase the system outright. On June 1, 1925, the utility became known as the City Water Board (CWB) and its management was placed under a Board of Trustees appointed by the city Council. At the time of purchase, the company was pumping an average of 25 million gallons daily to serve some 38,000 customers.

While struggling to develop an adequate potable water supply system, the city also attempted to address sanitary sewer needs. Mayor Bryan Callaghan II advocated an organized sewage system in 1890, but one was not authorized until 1894. By 1900, the system was fully operational. The original sewage collection effort divided the city into four districts and several sub-districts. A brick outfall main of 36 to 48 inches carried the flows to a sewage farm near the current site of Stinson Field.

In 1897, San Antonio had contracted with a private firm to handle the irrigation and land disposal of the sewage. When downstream irrigators became irate over the increased sewage load in the river, San Antonio contracted with another private corporation for additional sewage disposal. To contain any surplus, a dam was constructed at the south end of Mitchell Lake.

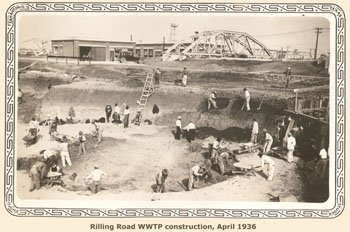

The same year the City Water Board was established, the city began preparations for the construction of the Rilling Road sewage treatment plant. In 1930, that facility began operation with a capacity of 25 million gallons per day (mgd). The plan used an activated sludge treatment method, and its treated effluent was routed by gravity to Mitchell Lake.

The same year the City Water Board was established, the city began preparations for the construction of the Rilling Road sewage treatment plant. In 1930, that facility began operation with a capacity of 25 million gallons per day (mgd). The plan used an activated sludge treatment method, and its treated effluent was routed by gravity to Mitchell Lake.

Flows into Mitchell Lake quickly reached capacity, especially during heavy rainfall. Due to complaints by downstream residents, the city took over operation and maintenance of Mitchell Lake. Modifications were made to the Rilling Road Treatment Plant in 1936, 1956, 1958, 1962 and 1966 to raise the facilities capacity to 105 mgd by the end of 1966.

Growth & Increased Water Demand

During the Depression and the war years, the City Water Board was able to keep pace with increasing demand without much difficulty. However, the post-war building boom and the impact of the 1950s drought significantly taxed the Board’s capabilities.

In the mid-1950s, the water operation utilized many widely scattered secondary pumping stations which were designed to serve immediately adjacent neighborhoods. These stations essentially operated independently and did not provide adequate system redundancy. Almost all the CWB pumps were set at elevations which corresponded to 623 feet mean sea level (msl) at the Beverly Lodges monitor well. In August 1956, the monitor well level dropped to 612 feet msl. The city Water Board had started an intensive process of lowering pumps, but the utility still strained to meet demand.

The Board of Trustees had authorized a contract with Black and Veatch Consulting Engineers to evaluate the water system and develop a master plan for improvements in 1954. Black and Veatch offered a series of recommendations which involved massive improvements to the Board’s operations. The original bond indenture provided that no additional bonds could be issued until all of the 1925 bonds had been retired. Since some of the outstanding bonds had a 1965 maturity date, no funds other than revenues were available for capital improvements financing. In order to modernize the water utility, a $21 million bond issue was approved by an election on June 22, 1956.

Applewhite Reservoir Project

Between the 1960s and 1980s, both the water and wastewater systems continued to expand as customer demand increased.

In 1965, the city built the Leon Creek Treatment Plant in order to ease the burden on Rilling Road. This facility had an initial capacity of 12 mgd and was later upgraded to a permitted capacity of 35 mgd. In 1970, the city added the Salado Creek Plant with an initial capacity of 24 mgd, and subsequently upgraded it to 36 mgd. Throughout much of this period, the City Water Board was involved in negotiations or court actions involving attempts to secure a supplemental water supply.

Then in 1979, a committee established by the City Planning Commission reported to the City Council that San Antonio should pursue the necessary federal and state permits to construct San Antonio’s first surface water supply project known as the Applewhite Reservoir. Shortly thereafter, the Council passed a resolution directing the Water Board to initiate the permitting process. The Water Board received the state permit from the Texas Water Commission in 1982, and the 404 Permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on Aug. 28, 1989. Construction on the lake began a few months later.

On May 4, 1991, the citizens of San Antonio – by a narrow margin – voted to discontinue the Applewhite Project. In the following months the trustees of the City Water Board voted to sue the city over the legality of the election. Court action subsequently upheld the city’s position and Applewhite construction was halted.

While water issues garnered the most attention, wastewater continued to be a demanding subject. During the 1970s and 1980s, the 208 Wastewater Policy Advisory Committee worked diligently to address the area’s needs. A significant result of that effort was the city’s decision to construct the Dos Rios Wastewater Treatment Plant and to abandon the problem-plagued Rilling Road facility.

Dos Rios opened in 1987 at a capacity of 83 mgd. The city also purchased the Medio Creek Plant from Lackland Water Company in 1991. This plant was built in the early 1970s with an initial capacity of 5.5 mgd and has since been expanded to 6.5 mgd. This acquisition allowed the city to provide service to the rapidly growing northwest portion of Bexar County.

No longer used for treatment, Mitchell Lake has been declared a bird refuge, and the city has assisted in the planning and the implementation of many ecologically sound and aesthetically pleasing improvements to the lake and surrounding properties. This unique and beautiful bird haven consists of the 600-acre Mitchell Lake, 215 acres of wetlands and ponds, 385 acres of upland habitat and is home to the Mitchell Lake Audubon Center.

Birth of SAWS

In 1989, the City of San Antonio asked the state legislature to pass a bill which would permit the creation of a district devoted to reuse of the municipality’s effluent. Senate Bill 1667, which established the Alamo Water Conservation and Reuse District, was signed by the governor on June 16, 1989. In 1991, the District applied for a permit to divert water from the Leon Creek Plant for reuse purposes. The City Water Board opposed that action due to its possible impact on the Applewhite permit.

The controversy brought on by competing water agencies prompted the City Council to vote in December 1991 to establish a single utility responsible for water, wastewater, stormwater and reuse.

The refinancing of $635 million in water and wastewater bonds made the merger possible. A new entity, San Antonio Water System (SAWS), was born May 19, 1992.

The refinancing of $635 million in water and wastewater bonds made the merger possible. A new entity, San Antonio Water System (SAWS), was born May 19, 1992.

SAWS was created through the consolidation of three predecessor agencies: the City Water Board (the previous city-owned water supply utility); the City Wastewater Department (a department of the city government responsible for sewage collection and treatment); and the Alamo Water Conservation and Reuse District (an independent city agency created to develop a system for reuse of the city’s treated wastewater).

SAWS also owns and operates – a separate utility – the former City Water Board’s chilled water and steam plant, which is a centralized heating and cooling system for the buildings in and around HemisFair Park.

In the consolidation, SAWS was also assigned the responsibility for complying with federal permit requirements for treatment of the city’s stormwater runoff. In addition, the water resources planning staff of the City Planning Department was realigned to the new agency to give it a complete package of related functions.

An important component of SAWS’ planning role is the responsibility to protect the purity of the city’s water supply coming from the Edwards Aquifer, including enforcing certain city ordinances related to subdivision development.

BexarMet Merger

Filed in 2011 by State Sen. Carlos Uresti, Senate Bill 341 set the course for merging the Bexar Metropolitan Water District with San Antonio Water System. After its passage in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, an election date was set for November 2011 when BexarMet ratepayers would vote on whether to dissolve the utility.

Filed in 2011 by State Sen. Carlos Uresti, Senate Bill 341 set the course for merging the Bexar Metropolitan Water District with San Antonio Water System. After its passage in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, an election date was set for November 2011 when BexarMet ratepayers would vote on whether to dissolve the utility.

The measure passed by 74 percent of the vote, and the U.S. Department of Justice approved the results in late January 2012.

SB 341 calls for the full integration of BexarMet within five years. It further allows SAWS to keep finances separate until a final merger can be completed without any adverse fiscal impact to SAWS customers or bond holders.

In addition, SB 341 calls for the creation of an advisory committee, which will provide input to the SAWS Board of Trustees during this critical time of integration.